|

The History Of

Great Sampford and Little Sampford

click on image to enlarge

The

contrasting villages of Great and Little Sampford have a

long history. Finds of worked flints at Great Sampford suggest a

Neolithic site

of some importance, scattered Bronze Age finds have been recovered and

ditches

probably associated with an Iron Age farmstead have been excavated.In

both parishes Roman

sites have been

discovered, of buildings with heating systems and heavy tile roofs but

considerably smaller than villas. These fit with the emerging picture

of the

Roman countryside being peppered with smaller farmsteads between the

great

estates of the villas. The river Pant runs through both parishes, and

its name

is a survival from the ancient brythonic tongue spoken before the

Romans

arrived that eventually became modern Welsh.

Essex was one of the earliest Saxon kingdoms and

this survival suggests

some kind of contact allowing linguistic exchange between the resident

Celts

and incoming Saxons.

Physical

signs of the Anglo-Saxons are hard to come by, though a few artefacts

have been

found in the fields.Interestingly,

however, the Freshwell Hundred (the local administrative district,

which in

some respects survived as such into the nineteenth century) which the

Sampfords

belong to is a late Anglo-Saxon creation.

Domesday records two manors held in the reign of

Edward by Wihtgar and

Eadgifu the Fair, suggesting that there were already two settlements.

One was

named as Sanfort, the other Sanforda – both probably

representing a

French-speaking clerk’s attempt to render in Latin the Old

English San Forda

or sandy ford – one of which survives in Great Sampford, and

is still

sandy-bottomed.

Both

villages are sited in Rackham’s “Ancient

Countryside”. Despitethe

loss of many hedges in the late 20th

Century, many of those that survive are sinuous with relict plants of

ancient

woodland such as dog’s mercury and wood anemone amongst their

roots, suggesting

that they are many centuries old.

In

fact the late John Hunter’s study suggested that most of the

medieval landscape

survived into the 1950s! The boundaries of the two parishes entwine

through

this and, until they were “tidied” in the

nineteenth century, each contained

detached enclaves of the other. These entangled boundaries and detached

portions suggest “intercommoning”, where residents

of both settlements had

rights to common land between them, and the boundaries of became fixed

around

these people’s plots when the parish boundaries coalesced,

probably in the 12th

century. At some time around this period, what is now Great Sampford

appears to

have been laid out according to a rectangular plan with the manor house

at one

corner, and the church across the road from the manor. This layout can

still be

seen today, despite one side of the rectangle never being developed,

and despite

later encroachments across the centre line of the plot. On the other

hand,

Little Sampford remained a series of straggling hamlets and the church

and

probable manor site, although adjacent to each other, at some distance

from the

nearest settlement.

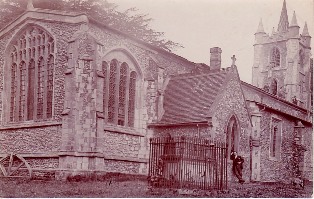

In 1096

William Rufus granted the church of St Michael at Sampford Magna (now

Great

Sampford) to Battle Abbey, and it was to become the seat of a Rural

Deanery,

covering twenty-one parishes. This importance, and the wealth of the

abbey, explains

the enormous church in such a small village. Apart from the

thirteenth-century

south transept almost the entire structure dates to between 1320 and

1350. Almost

no addition was made to the church after this date. Battle Abbey had

long since

stopped maintaining it by the Dissolution and the neglect continued so

long

that, even after Victorian refurbishments in the 1840s and 1870s, the

parish

was unable to roof the nave in anything better than corrugated iron. St

Mary’s

at Little Sampford, on the other hand, appears to have evolved

piecemeal over

the centuries. One notable break in construction can be seen in the

mid-fourteenth century tower, which is popularly attributed to the

Black Death.

Here the living was attached to the manor, rather than a distant abbey,

which

may explain the continued development of the building.

There are

other medieval relics as well.A

number

of farms retain the names of their owners, with Free Roberts bearing a

name

recorded in 1258, whilst the record-holder in Little Sampford is

Hawkes, first

recorded in 1280. There are also a number of moats, sites

of moats, within the two parishes. Some

of these, such as at Howses, still enclose a house whilst others do

not. Most

are thought to be of 13th or 14th

century date, and would

probably have been dug for display, and to supply fresh fish, rather

than for

defence.They

suggest prosperous

settlers, able to expend money on building status symbols. A second

wave of

moat digging occurred in Tudor times as arrivistes sought to give their

new homes

a respectable air of antiquity by surrounding them in medieval fashion.

At

around this time a deer park was created at Little Sampford and a

mansion built

in brick. The park has reverted to arable land and the house was pulled

down in

the 1920s but the outline of the park can still be traced and many

features of

the ornamental garden survive in the grounds of the

“new” Little Sampford

Hall.

Several

houses survive that predate the Tudor hall, in both parishes. A

sprinkling of

sixteenth century houses and a plethora of seventeenth and eighteenth

century

ones demonstrate the relative prosperity of these centuries, when the

Sampfords

were weaving villages. Ironically they also show the poverty of later

times,

when there was not the money available to pull down and replace with

the latest

style.

A number of

“personalities” passed through the 17th

and 18th century Sampfords.

Colonel Jonas Watson, Chief Bombardier of England, is commemorated by

an

obelisk in Great Sampford churchyard, killed on active service aged 77,

whilst James

MacAdam, son of the inventor of tarmac,

and Arthur Young, famed writer on agricultural matters and multiple

failure as

a farmer, both lived at Little Sampford Hall. The most lasting legacy

of these

landlords are the churchyard wall and lime trees at Great Sampford,

planted by

General Eustace who, having carried a silver plate in his skull since

the

Peninsular War, in later years insisted on riding his horse up the

stairs to

bed each evening! Elsewhere, Henry Hebblethwaite inoculated parish

children against

the pox, and may well have spent time in the West Indies for his

brother’s

children (by a slave mother) sued for a share in his estate.

If the population is anything

to go by, the Sampfords were

relatively prosperous in the early nineteenth century. In 1801 Great

and Little

Sampford had 597 and 346 inhabitants respectively. By 1851 the figures

were 906

and 471. In the centre of Great Sampford, the Red Lion Inn was built

around

1830, and suggests that someone had plenty of money to erect such a

fine brick

building. However the figures oscillated through the later nineteenth

century

as agricultural depression bit and in 1901 the population was 496 and

296, with

many people leaving for the towns, especially London, as the ease of

travel

increased. In 1875 the School Board had to defend themselves against an

accusation that they had over-estimated the number of pupils they had

to

provide for by pointing out that a mass exodus had left twenty cottages

uninhabited. Here was no rustic idyll. The 1871 census recorded 9

people living

in sheds, and disease was rife with cholera striking in 1866 and

typhoid

several times in the 1870s. Improvements were being made, however. A

school was

built in 1870 and, for reasons of politics, was replaced by the current

building in 1878. At long last Sampford children were to experience the

benefits of universal education.A

fine

new Baptist Chapel was also built at much the same time, in the midst

of the

depression and exodus.

It was two denuded

villages that greeted the 20th century.

Of 285 houses in the Sampfords in 1851, only 184

were inhabited seventy

years later. On the other hand, despite general depression agricultural

labourers were doing well. So many had left for employment in the

cities that

those who were left could name their wage, and many were able to take

up small

farms as a result. However 1914 bought war on an unprecedented scale.

The two

parishes record 26 names on their war memorials and many more must have

served.

Sidney Gowlett returned home with a Distinguished Conduct Medal and

Walter

Schwier with the Military Cross, the latter having taken part in a

cavalry

charge in 1917. The schoolmaster Harold Blayney, feared and respected

in equal

parts by the pupils he thrashed, inspired similar fear in recruits

before

making his way to Palestine in time to witness the collapse of the

Turkish

army, while brothers Jim and Bill Gray tired of waiting to be liberated

from

POW camp whilst Germany crumbled round them and simply made their own

way home.

Although

some new houses were built along the Thaxted road in the 1920s, they

did not

return home to a land fit for heroes. Agriculture had prospered during

the war,

with cheap grain from North America restricted by U-boats. But prices

crashed

in 1921 and farming entered a deep slump that it would not recover from

for

nearly twenty years. The 1920s and ‘30s were characterised by

poverty and

struggle, with peopling leaving the village. In 1936 Jim Gray was

offered £100

or a cottage in his uncle’s will, and took the money because

he would not have

to pay for its upkeep! Tithe was seen as an iniquitous tax, and at

least three

Sampford farmers took extreme measures, having to be prosecuted before

they

would pay. It was also at this time that the middle-class

“invasion”

of the countryside began. Gerald

Miller became the first commuter, writing a column on rural matters for

the

Times, and artists and intellectuals such as Olga Lehmann and Alan

Rawsthorne moved

in. Holidays in Great Sampford even inspired the Reverend Graves to

found the

legendary Dagenham Girl Pipers!Agricultural

subsidies began to effect a recovery in the late 1930s, and much work

was done

to shore up the crumbling fabric of Great Sampford church in 1937.At

this point the Tudor

stair that English

Heritage insist to this day is still there was removed from the tower.

However war

once again reared its ugly head. On September 2nd

1939, 150 women

and children were evacuated to the Sampfords from London. Many soon

returned,

but a number of city children spent several years there.Given that the

children

were supposedly

evacuated to “safety”, it is sobering to think that

farmers were given

instructions on how to destroy anything of value to the enemy, and at

least one

family kept their suitcases packed in the hallway.

In fact, one of the “Stop Lines”

– rows of

fortifications that were supposed to delay the progress of the Nazi

invaders -

defending London passed right through the Sampfords!

This was manned by the local Home Guard –

eventually, for the building chosen for their command post could not be

used

until the shopkeeper’s hen had hatched the brood it was

incubating there!Some

200 bombs fell in the villages, including

at least two huge parachute mines, and on August 26th

two German

airmen, parachuting from their burning bomber after a raid on RAF

Debden,

landed at Great Sampford where they were captured. They fared better

than a

squadron-mate who, landing at nearby Finchingfield, broke his leg when

he hit

the war memorial! Later that year, construction began on an airfield

called RAF

Great Sampford, but in fact lying almost entirely within the parish of

Radwinter.Perhaps

the oddest legacy of

the war was, for many years, a hymn in “Ancient and

Modern” to the tune

“Sampford”, the work of John Ireland who spent the

war years at Little Sampford

rectory.

Thankfully

the invasion never came.After

the war

agriculture remained profitable, and the village seemed to be

thriving.However, as economics

became more and more

important, and as mechanisation progressed, the number of men employed

on the

land became fewer and fewer. Larger

and

larger machinery came in to try to speed harvest, and to have grain to

sell

before the market was glutted and the price collapsed as it does each

harvest.As a

result fields were amalgamated and

hedges grubbed out, making a substantially more open landscape than had

been

the case previously.There

was also less

employment in the village, so people moved away into towns.

Meanwhile

the population of Britain was becoming increasingly middle-class, and

affluent

enough to afford the urban ideal of a house in the country.As a result

of this

cross-traffic, the

Sampfords have increasingly become dormitory villages for commuters.The

rise of supermarkets

has meant that

shops, pubs, and a village garage have closed, leaving a single pub and

a

garage in Great Sampford as the only local

“necessities”.There is little employment in the

village

itself and, ironically, the airport that threatens the area is probably

the

biggest employer of Sampford people.House

prices continue to reinforce the middle-class nature –

remember the £100

cottage in 1936? They have increased by thousands of percent since!

– and few

young people growing up in the Sampfords are likely to be able to

afford to buy

a house there.However, the picture is

not all doom-and-gloom. The two

village cricket clubs merged in the 1970s and Sampfords Cricket Club

have

recently purchased the ground they have played on since then.There is

also a Sampfords

Society who have

been very active in Local History, and who were involved in Heritage

Sampford,

an ambitiousproject

to map the

archaeology of both parishes. This has provided much of the historical

information

here.

Adrian Gray

|